Gamelan Making

On our last day in Solo, we visited a gamelan-making village outside of town. With vague directions from the hotel staff, we mounted rickety rented bikes and pedaled our way through the traffic and fumes towards the outskirts of town. As we passed a roadside market, a group of goats sitting on a truck stared back at us. Where town ended, rice paddies began, a vast expanse of vibrant green and yellow crisscrossed with canals and low bridges. After a few turns, we were lost in a small village. The locals pointed down the street, and as we approached a small, unassuming brick building we heard the sound of hammering. A group of men were crowded around a gong, pinned to the ground with a wooden lever, pounding it into shape with an oversized wooden mallet. The sound was deafening. The friendly workers, excited to have guests, invited us to look closer. The boss showed us to a small room where a few finished gongs, made of copper and tin, were lined up, ready to be shipped. Orders came from all over Indonesia – even Bali, where they did not have the expertise to make the larger gongs. Did we want to order one? Only 16 million rupiah (about $150) for a 90 cm gong, but he could lower the price! We assured him that we only wanted to see how the gongs were made. In a small, narrow alley next door, a boy polished a smaller gong with a buzzing rotary tool. The pounding stopped, and the workers proclaimed the gong finished. They moved inside to the smelter. A man squatted on the floor with a sack full of old speakers, motors and generators, a cheap source of “recycled” copper. He dumped the bag on the dirt floor and selected bundles of copper wiring to put on a scale. The boss, scratching some calculations on a dirty scrap of paper, made a mark on a dull, silvery hunk of metal. We weren’t really sure if it was lead or tin or a mixture that was being added to the copper – the word “timah” in Indonesian means both! From the high price, however, we assumed it was tin. The boss told us that special customers requested that silver be added as well, to improve the sound.

|

|

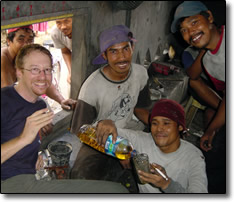

Piles of charcoal were everywhere. It was impossible to stay clean with the dirt, grime and dust. The workers, walking barefoot around the “pits”, stoked the fire. A pile of black ashes sprang to life, glowing red-hot. A length of rebar, heated in the fire, its tip glowing a dull red, was used to cut the morsel of tin into two pieces. The scrap metal was put into a ceramic crucible, then placed in the glowing pit and covered with charcoal. The workers, walking cautiously with their bare feet, poked and prodded the fire as sparks blew in the air. The mold, a flat, round impression in the ground, was carefully swept clean in preparation for casting. The men gathered around, nervously anticipating the crucial operation of pouring the red-hot molten metal into the mold. When the stoker deemed the mixture hot enough, the men, holding tongs protected by gloves improvised from banana-trunks, picked up the crucible and poured the fiery liquid into the mold. Impurities, floating on the surface, were scraped off with a metal bar. Rice husks were thrown over the cast to form a protective layer. They immediately turned black and started smoking. The casting completed, the atmosphere became relaxed. Plus, today was payday! The boss gave everyone his weekly wages, about $15. One of the workers proposed getting some “medicine” to celebrate Eric’s birthday. Why not? Eric was ferried to the local copy-shop by one of the men on the back of his motorbike. Discretely he bought a bottle of the local specialty, a kind of ginseng liquor mixed with beer, from the back room. A bag of “krupuk” (chips) and the party was on. Everyone laughed as one of the younger men, having drunk too much too fast, went around the corner to throw up. We said goodbye to our new friends and pedaled wearily back to town. In Indonesia, junk is recycled into beautiful gongs.

|

|